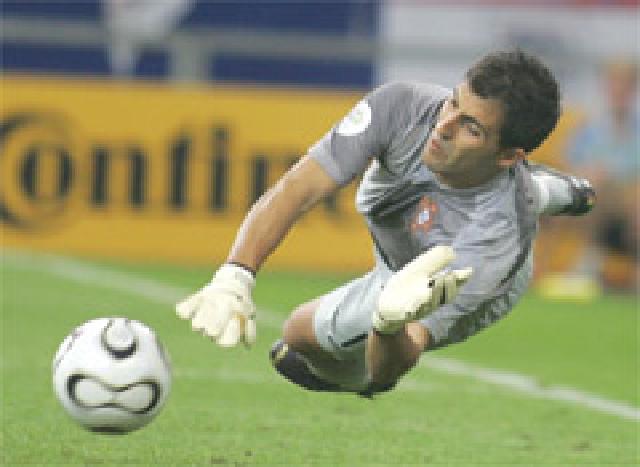

Portugal v England

As is perhaps to be expected in this day and age, everywhere you look at the moment there’s football, football, football. The World Cup is more than just a spectacle, it’s a regular event and therefore presents an opportunity. An advert which doesn’t in some way link the Beautiful Game to washing powder, mortgages or anti-wrinkle cream is almost refreshing. Of course, the World Cup would not be so all-pervasive without the weight of corporate advertising and media on the bandwagon, but there are some underlying psychological effects, which are being harnessed as only corporate business knows how.

Just think how many millions view the games, particurlarly of the home nation; viewing figures suggest around 19 million households tuned in to watch the England v Portugal match, and that number masks the people watching with friends, at home or in public. Of course, cutting away the naturally avid football fans leaves a significant number simply watching to support their national side, but how does this turn into something of a fever? The rampant nationalism provoked at times staggers belief, and often goes far beyond the football itself. Finding sensible criticism of England’s performance at the World Cup is some achievement, whilst in the immediate aftermath of England’s exit, jingoistic slurs against Portuguese players and Argentine referees were on the tip of many tongues.

This form of English nationalism is so deep that not even the other home nations are spared its often abrasive and provokative forms. But why does it exist in the first place? It is clear that the fortunes of the England team ultimately have no relevance on the lives of the vast majority of the population, and yet somehow this has been linked in their minds such that England’s success gives rise to feelings of joy. The effects a victory can have on the supporter have been studied , with the release of serotonin causing pleasure through victory. This is more than just pride in one’s nation of birth, or a strong case of empathy. England’s dismissal caused a great deal of anguish for many supporters: the fact that it was once again on a penalty shootout only heightened the sensation. As if to soften the blow, ITV’s commentator Clive Tyldesley reminded viewers a number of times during the Germany v Italy semi-final match that at least there was still an Englishman in the World Cup, albeit under the name of Simone Perrotta, born in Ashton-under-Lyme (coincidentally the birthplace of Geoff Hurst).

First it is me and my clan against the world, then me and my family against my clan, then me and my brother against my family, then me against my brother.

Somali Proverb

It would appear then that support for one’s national football squad might aptly demonstrate one of mankind’s vestigial ‘pack’ instincts. As the Somali proverb illustrates the various levels of a man’s supposed priorities in life, so we must understand how through association with a greater whole, an individual can hope to benefit. This might be interpreted as a behavioural imprint, as an individual learns that what is good for his family is good for him and so on, yet its wide presence in the animal kingdom can only suggest this is an ‘instinctive’ characteristic. Assuming this natural neuro-chemical reward system were still present in the human species, is it possible that it makes its appearance unacknowledged, yet slightly altered from its natural designs? Is empathy itself an expression of our ability to mould this built-in system and produce a sense of symbiosis with other individuals and groups? People rarely question why individuals choose to support their national football team, and obviously patriotism plays a large part in this, yet it is commonplace to find people who support football clubs different from the places they work, live or grew up in. In the case of many Irish people, for example, these are clubs in an entirely different country from the one they live in.

This form of association or ‘support’ is by no means isolated to football, being seen in some form or other in many of the other walks of life, as people buy a certain brand or read a certain author. Of course in these instances there is a large case to suggest that this support is very calculated and personalised. Yet this does not prevent glimmers of an underlying associative instinct shining through; the normally shrewd ‘intel’ supporter buys a chip from his corporation despite the universally acknowledged benefits of its cheaper and technically superior rival. Why? For the simple reason that he has unknowingly linked the fortunes of the intel corporation to his own life, and what’s good for them will be good for him.

Football jingoism could of course simply be a case of societal patriotism combined with a heightened sense of empathy for the players, yet their performance seems irrelevant to the feelings held by many of the supporters. Victory is the goal, the only source of the ‘feel-good’ factor, and the Beautiful Game can suffer at its synapses.